‘When I missed home most, cooking helped’: Baneta Yelda, baker, Manchester

I studied biology in Iraq for my undergraduate degree and worked in a pathology lab. In my 20s, I fled the place where I was born and raised, when Islamic State were advancing. I arrived in the UK in 2014, only intending to stay for a week, but I became a refugee. Living in London I took a job working for the NHS. I loved being part of the health service, starting as a lab assistant before moving on to train doctors and nurses.

Like most people who move to the capital, I flat-shared. I often cooked for my housemates and my colleagues, too. It was a way to show love and to express my creativity. Plus, my mum is a very good cook. I grew up eating wonderfully. In London, I’d spend my weekends making Iraqi meals to share with the guidance of my mum on FaceTime. The smells and flavours of Iraq filled the kitchen. When I missed home most, cooking and food helped me stay in touch with my heritage.

At first, cooking casually was enough. But I wanted to try and learn more. So, at 27, I took a few days off work and approached some restaurants about doing some work experience. A new Middle Eastern restaurant offered me a gig helping them develop dishes and design the menu. From then I did bits of freelance food work on the side, all the while still working at the hospital. That’s when I heard about the School of Artisan Food in Nottinghamshire and their annual refugee scholarship with a charity called Tern. I studied for a diploma there, an intense, six-month commitment. Most of the course was baking – patisserie and viennoiserie, too.

Baking made total sense to me, far more than the fast-paced speed of restaurant kitchens. It’s a humble craft, which takes patience and time. It slowed me down, changing my perspective on cooking. It’s there that I met Neil, now my business partner. He was on my course, having previously worked in construction. Once my studies were over I was working in an east London bakery when Neil called to say he and a friend were taking over a bakery in Manchester – did I want to be part of it? After one visit I said yes and moved up north.

That was three years ago. It hasn’t always been easy. At Campanio, we’re a small neighbourhood business with a real community feel. We do all sorts – sourdough, pastries, lunches. And we supply businesses from little cafés to a Michelin-starred restaurant. Developing new recipes is still my favourite responsibility. Opening the doors was a challenge, then lockdown came along. Now, we’re grappling with energy and food prices, and the economy. But I have not a single regret. My family is of Assyrian heritage, have been through a lot and are spread all over the world – before Isis we were fleeing genocide. We’ve learned how to create home in ourselves, rather than relying on a specific location. Through my recipes and our bakery that continues.

‘Tonight? Well, we’re fully booked again’: Aji Akokomi, restaurateur, London

My parents were always clear – ours was a family where the children would go to university and enter academic professions. With no room for negotiation, that’s what I did. Born and raised in Nigeria, I came to the UK to study for a master’s in business administration. From there, I started to work in IT. I enjoyed the job, sure – planning and delivery suited my personality. Yet there was something missing, an itch to be creative and independent in my work. Back at home my mum worked in food. I’d always imagined one day I might return to Nigeria and follow in her footsteps. Still, life happens: I got married here, had a son, made a life and took on responsibilities. Then one day it dawned on me – why not try to create a food business here instead?

Food had always been a passion, taking up most of my headspace. When throwing dinner parties I’d often lose whole days in the buildup. Most of my friends came from different backgrounds. When they’d eat my food, they’d always comment on how the flavours of west Africa excited them. Maybe, I thought, I could turn this into a business with legs. My USP? A fine-dining restaurant exploring and elevating the food of west Africa.

I signed up for a 10-week evening course at Leiths cookery school. It was full on – three nights a week I’d head to classes right after work. I learned the fundamentals of a kitchen and how a restaurant works. It gave me the confidence to take the next steps. I turned my house into a development lab and test kitchen, working with consultant chefs to take recipes from home – the food of my mother and aunties. We used grains of paradise, yam and plantains; ehuru (African nutmeg) too. We served jollof rice, suya and miyan taushe.

Investors were hard to come by, they saw our concept and cuisine as risky. Landlords were reluctant to take a punt on someone so new to the food industry, too. And I hadn’t gone the traditional route – I didn’t spend years in culinary school, I never worked inside other people’s businesses. I did it my own way. It has been a real challenge, but I made it happen. And tonight? Well, we’re fully booked again at Akoko – my restaurant just off Oxford Street, which serves a tasting menu of west African food.

‘On my flower course, I came back to life’: Clara Barthorp, florist, Jersey

It’s been 10 years since I did my floristry course. I started out my working life as a teacher before moving into interior design in London. I returned home to Jersey and continued working, though soon it had to be juggled with single parenthood and three small daughters.

Out of the blue, circumstances meant I had to leave my job and turn my attention solely to the children. It was a challenging time, raising my family, unable to work. I was at home all the time, so people started to leave their dogs with me when they needed caring for – my mum, a neighbour, the vicar. I set up a small dog hotel business, Pet and Breakfast, in our home. My own career aspirations took a back seat, but it suited my parenting setup. Although I was able to provide for my family, it was soul-destroying not being creative – and having my home trashed by dogs regularly. Once the girls reached nine and 11, I knew I had to make a change. I knew I wanted to work with flowers.

It just made sense really. When I was little, my parents had a beautiful garden. I’d steal their roses and make potions in the bathroom. As a young adult I’d stand in the doorways of flower shops transfixed by what I saw.

I researched hard looking for a place to train and settled on the Tallulah Rose Flower School. There was a four-week course on offer, which – due to my childcare responsibilities – they agreed to squeeze into three if I worked hard. The preceding years had been tough. A bleak time, professionally and personally. On this course, I could breathe again and came back to life. I was taught business and pricing, caring for and processing flowers, and the mechanical elements to floristry. But mostly we were left with a bucket of flowers and encouraged to explore and create. Through that I found my own style. Back in Jersey I got my business going. Now I also have a shop and a small team. Every day I’m grateful for the opportunity that course gave me.

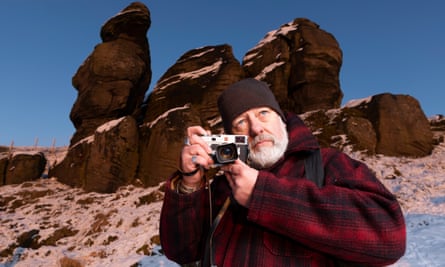

‘Adult education is a gift, it changes lives’: AJ Wilkinson, photographer, Hebden Bridge

I left school at 16 with barely any qualifications. Most work I could find paid very little, so I did all sorts, then I found a job as a porter in a hospital geriatric ward. Music was my life back then, but I’ve never played an instrument. I wanted to find a way to feel part of the scene. I picked up a camera with little thought – a cheap point-and-shoot job – to try and cement a role for myself, taking pictures. It was on a whim, really, that I decided to try and learn more about photography.

That’s how I stumbled upon a local college course. I went to classes one evening a week and learned the basics. My first course lasted 10 weeks – before the end I’d enrolled on another. Each one focused on a different skill – there was aperture and composition, darkrooms and exposure. I enrolled on a daytime course in another part of town, part-time, when I’d completed all the evening options available.

Dad was a plumber, Mum was a bookkeeper and lollipop lady. I’d never done anything artsy before – there hadn’t really been an opportunity. Meeting other students on the course – from all backgrounds, with all sorts of experiences – made me realise maybe I did have something to express, ideas to explore and share.

I was still working in the hospital through this time. Management gave me free rein to take pictures in its buildings. In my spare time I was learning all about documentary photography and at the hospital I put it into practice. Photography became my world. Two years later I took the plunge and set up shop as a full-time photographer. My practice grew from there.

Ten years after I first attended night school, I had a conversation with my old tutor. He was planning to leave and thought I might be a good fit to take over. A decade after I’d first stepped foot in the college, I found myself standing at the front of the classroom. I’ve continued to teach ever since, studying for my own MA in fine art along the way.

Adult education is a gift, it changes lives. But in recent years cuts have seen access to it decimated. By 2025 there’ll be £1bn less in adult education than there was in 2010. Not everyone grows up in an environment full of options, others take a while to find their calling. Something has to change, and rapidly, or else someone like me would never have the opportunities

to do what I’ve done.

‘I immersed myself, learning a whole new skill’: Deborah Brett, ceramicist, London

It’s still new to me introducing myself as “Deborah Brett, ceramicist”. I used to have to list all sorts of things to explain what I did for a living – finding the right descriptors was a real task. I started out as a fashion editor. I worked as a stylist and writer.

After having my third child, nine years ago, I’d been in fashion for almost two decades. I could do it with my eyes closed. I needed a new challenge – the next frontier. As a parent you look at your kids and think, what is going to ignite their passion? How can I help them find it? We actively expose children to new opportunities. As adults we deny ourselves this, falling into a pattern of do and repeat. I decided to create the same space for myself.

I gave myself a year to try all sorts of new things: printmaking, flower-arranging, baking. You name it, I gave it a go. By figuring out what I didn’t like I thought I might stumble upon what I could love.

I must have been mumbling about all this in front of my parents-in-law because for my birthday they bought me a short ceramics course. I went along and over a few evenings fell in love. I promptly bought another course, then the next one. It snowballed. As my interest developed I found a new set of night courses at a local adult education college. Soon, my tutor was suggesting I do a BTec. I was tentative, signing up for a year-long, two-days-a-week course on top of a job and parenting. But it was phenomenal. Under the tutelage of Nam Tran – of Great Pottery Throw Down fame – I immersed myself in this world, learning from scratch a totally new skill.

In lockdown I made my first collection for a hotel on my kitchen floor. Since then I’ve built my own studio in the garden. I’d be in there every day if I could, experimenting with shapes and glazes. I launched my own range of tableware, working with a factory that handmakes the pieces. I now have a website where I can ship all over the world. And there’s so much more. My brain is constantly buzzing.

It wasn’t just the craft I’ve found myself exploring. As adults we learn to be jugglers, always balancing responsibilities and priorities. For a long time I saw multitasking as a superpower. Now I think it’s one of the worst things I can do. Ceramics has taught me to focus on one single thing at a time, to give each moment my undivided attention. Without that ethos, no piece will prevail. And even then most of what you make won’t work so you really must learn to embrace failure. There’s something liberating in teaching yourself to let go.

‘Now I’ve tasted freedom, I’ll never go back’: Ben Spence, cheesemaker, North Yorkshire

The days are long if you’re a cheesemaker. By 5am, I’m driving to a nearby farm to collect milk in our trailer from a neighbouring farm. By 7am, it’s warming while we have breakfast as a family. By 3pm, however, most of the process is complete. I worked in accountancy before we started Curlew Dairy – both jobs have their challenges. But making something of our own and doing it on our own terms? Now I’ve tasted the freedom I’d never go back.

I grew up on our family dairy farm in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire. It was a run-of-the-mill affair – 60 or 70 cows – nothing compared to modern factory farms. I studied agricultural business management at university although my heart was never in it. I spent the next seven years working in the Manchester office of a major accountancy firm. I’ve no regrets about that time – it’s where I met my wife, Samantha. When we started to contemplate starting a family, though, I knew I couldn’t stay. Deep down I wanted to be working with my hands. Instead, I was behind a desk 12 hours a day. I had all these memories of my dad being around at breakfast and lunch when I was growing up, doing the school run, making the business work around family life. I wanted that, too.

So we returned to Yorkshire. We needed to find a way to diversify, making the farm sustainable. When I started sounding out advice from others locally, there was a suggestion we turn to Wensleydale cheese.

Seven odd years ago, Sam (while heavily pregnant with our first child) and I enrolled on a one-day cheesemaking course at the Courtyard Dairy in nearby Austwick. The course was a springboard for so much afterwards. It was the network of support we left with, really, which was the greatest education – the expertise of our tutor, Andy, and our fellow students starting out on similar cheesemaking journeys. It’s a world away from the cutthroat nature of finance I’d previously known.

With the support and generosity of our community – locals and the people we’d met on our course – we set up Curlew Dairy. We make a traditional, unpasteurised Wensleydale out of our garage. It’s hard work, undoubtedly, and keeps both of us busy. But whenever I need to, I can step out and spend time being a dad.