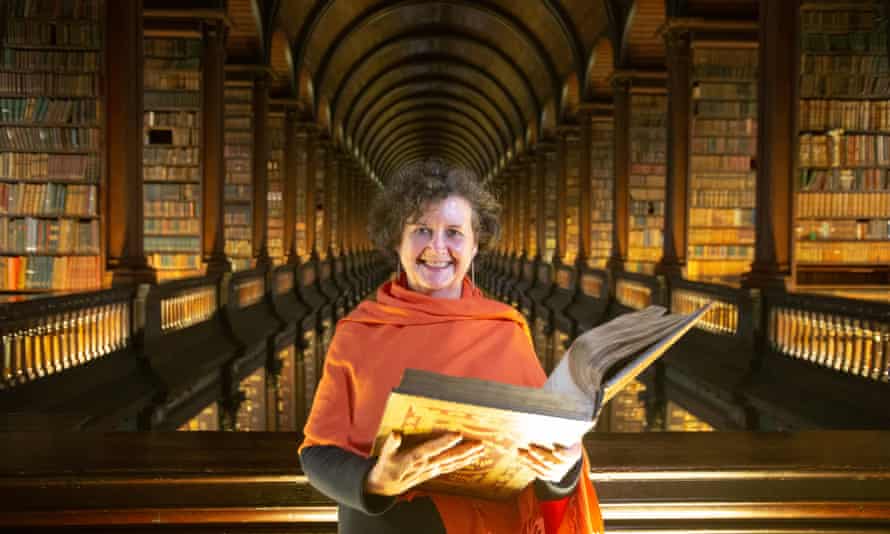

It is known as Ireland’s “front room”, where esteemed visitors including the Queen, Joe Biden, Emmanuel Macron and the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have been taken to get a sense of the “land of saints and scholars”.

Biden, vice-president at the time, was so moved by the atmospherics in the dimly lit, barrel-vaulted hall when he visited Trinity College Dublin (TCD) in 2016 that he came back a year later to contemplate the history of its old library, known as the Long Room.

But if he makes a third visit, he may not be so lucky. Three hundred years after the first foundation stone was laid, the 250,000 ancient books and manuscripts – including the ornately decorated ninth-century Book of Kells – printed on vellum, paper or silk are to be moved one by one, along with 500,000 others, to make way for the restoration of the building.

It is a monumental task that will take the best part of five years and cost €90m (£75m).

“Moving 750,000 vulnerable books is quite an undertaking, so we are having to pilot everything to see what is involved,” says TCD’s librarian and archivist Helen Shenton, who is leading the daunting project involving a 50-strong team.

Some of the books in the alcoves that line the 65-metre hall are so delicate they are joined together with fabric ties. The accumulation of exhaust fume particles from the roads surrounding the building can accelerate the deterioration, while human detritus from nearly 1 million annual visitors pre-pandemic, ranging from clothing fibres and human hair, reaches 1cm in parts.

Each book has to be examined, dusted, carefully hoovered and repaired if necessary. In a normal maintenance and preservation cycle “it takes us five years alone to clean all the books”, Shenton explains.

The restoration project is currently in an “enabling” phase that will last two years because of the fragility of the books. It will determine the logistics of the move and the equal challenge of keeping the collection of books open to students and visiting scholars.

The physical preservation of the books is the driving force behind the project. Recent fires at Notre Dame, the national museum in Brazil and the Mackintosh building at the Glasgow School of Art have shown the risks to historic and cultural buildings.

“We do not want to join that litany,” says Shenton. “We need to conserve the building and the collection for its fourth century,” she said.

Even the distinctive smell that Shenton says many visitors remark on when they enter is evidence of deterioration. According to a book on the library by Harry Cory Wright, the sweet scent is “the smell coming from ageing cellulose in paper, similar to the smell of almonds, which contain the same chemical.”

Shenton says: “Books are organic artefacts and what you are smelling is deteriorating leather, deteriorating paper, and the thing we can do to slow that down is to have better environmental conditions. Not only do we need temperature and humidity control, we also need to protect against particle pollution that is coming through the windows.”

The restoration has been on the cards for years, and cataloguing each book was finally finished during the pandemic with a team of 50 working from home, completing what was a 40-year project.

To future-proof the collection for study, Shenton is also creating the first online catalogue of Trinity’s collection. Each book will be fitted with a radio frequency identification (RFID) tag to enable scholars to be able to target their reads from the comfort of their desks.

Once all the books have been removed, the library will close for about three years, during which time the building, under the plans of heneghan peng architects, will undergo a complete makeover.

In what will be a shock to many previous visitors, the ground floor will be returned to the open arcade of the original building, which was designed to protect the books on the first floor against damp.

At the same time there will be “a completely reimagined exhibition” that will position treasures such as the Book of Kells in an international context, exploring for example “what was happening on the Silk Road at the same time”.

And finally, the male-only series of busts, remarked upon by Meghan, that stand at each of the alcoves in the Long Room is also going.

It was one of the first things Shenton noticed when she took the job and, after a competition, four new busts by four different artists will be commissioned, of the mathematician Ada Lovelace; the Abbey Theatre co-founder, Lady Gregory; the writer Mary Wollstonecraft; and Rosalind Franklin, the biophysicist who made critical contributions to the identification of the double helix structure of DNA and related RNA.