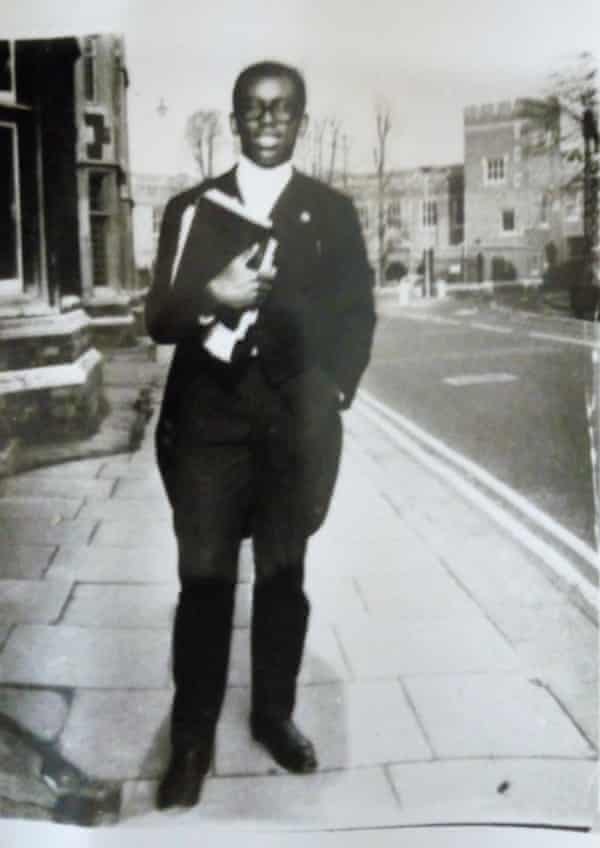

As soon as Dillibe Onyeama was born, in January 1951, his father put his name down for Eton, the UK’s most prestigious and expensive public school. No black child had gone there, but his father, a senior judge in Nigeria who had studied at Oxford, wanted him to have the best education he could possibly afford.

Onyeama did go on to receive a fantastic education – and made history as the first black person to complete his study at Eton College. But the personal cost was staggering.

Today Onyeama remembers the immense pride he felt when he first got in, and in the first few days he was confident he would enjoy being at the school. He wrote to reassure his father, and his guardian, the Reverend Arthur Cox, who had warned him he might have a difficult time. But he spoke too soon, later writing “there were many occasions when I regretted those words – bitterly”.

His awakening came a few weeks into his first year studying with the children of the British elite, when the 14-year-old was greeted by ape noises and racial slurs when he entered his classics lessons. The taunts surrounded him. “Here comes the big black bastard,” one boy shouted, as others jeered. When he quietly asked what they were doing, his peers responded with more ape noises. So he sat down and tried to ignore them until a boy approached to ask if he felt ashamed wearing school uniform; when Onyeama asked why, the boy responded: “I thought that, since all Africans usually wore nothing, wearing this would make you feel ashamed.” Cue a louder chorus of laughter. He tried to explain that Africans don’t walk around naked, but it fell on deaf ears.

In his four years at Eton, between 1965 and 1969, Onyeama was often verbally abused, called a “wog”, “nig-nog” and the N word. Shortcomings in his school work were attributed to him being black. Even when he did well, in sports, for example, he was told it was down to the so-called unnatural advantage his race afforded him. Onyeama wasn’t completely surprised by the racism he was forced to confront at such an early age, he tells me, because “Eton is built by English royalty, and that’s the first place that supremacist attitudes exist.”

Nearly 60 years since he first stepped into Eton as a school boy, Onyeama’s shocking experiences are once again laid out in his frank and reflective memoir: A Black Boy at Eton. First published in 1974, it is set to be re-published by Penguin as part of its Black Britain: Writing Back series, an initiative by Booker prize winner Bernardine Evaristo to reprint hugely important books by black British writers that have since disappeared.

Onyeama was born in Enugu in eastern Nigeria, the second eldest of seven children. His father, who lived in the UK for five years, was a magistrate (and would go on to become a supreme court judge in Lagos). It was while he was at Oxford that he heard of famous public schools like Eton, Harrow and Winchester, and, because of his great respect for the British education system, resolved to send Onyeama there.

Onyeama describes himself as an “extremely sociable” child who mixed well with other children. When he was four, he was sent to live with his uncle, because his father was often posted to different parts of Nigeria. He loved playing football in the street and playing pranks on unassuming adults. Those early years were idyllic, with his favourite memories of time spent with his family in Lagos.

Then, when he was eight, he was told he would be sent to England to go to a prep school. “My only knowledge of England was that it was a white man’s country and was very cold, and I wasn’t at all enthusiastic to go there,” he writes in his memoir. His parents gently turned down his protests, and, next thing he knew, he was on a ship steaming across the Atlantic.

Two weeks later he joined Grove Park, a prep school in the Sussex town of Crowborough. He was the first black boy to attend that school, but had a wonderful time, facing no racism. “I suppose because we were all too young to know about colour prejudice, and that such a thing existed. I certainly had no notion,” he wrote. The students and teachers were caring – and supportive of his ambition to go to Eton. “I’m still in touch with my friends from there. It was a beautiful place, with beautiful people. They were great ambassadors of the English,” he says.

Onyeama initially failed his entrance exam to Eton and, to his horror, another boy – Tokunbo Akintola, the son of the western Nigerian prime minister, Chief Samuel Ladoke Akintola – made headlines in 1964 when he became the first African boy to pass it. His dad was disappointed and it was agreed that he should leave Grove Park and go to a crammer, a specialised school that trains its students to pass certain entrance exams. He was sent to Beke Place and worked flat out in preparation for his second attempt at the exam.

When he learned that he would be going to Eton, he was thrilled. “It was something he [my father] was invested in from birth,” Onyeama says. “He said: ‘Well done, work hard … fit in well, obey your superiors.” His excitement palled when a student at Beke Place told him he wouldn’t be very popular because he was black.

He started Eton on 19 January 1965, just two weeks after his 14th birthday. It was a “grey, cold and miserable” day and he was racked with nerves. In the dining room for his first Eton breakfast, “A sea of moving white jaws became gapingly still as I entered,” he writes. “Almost complete silence momentarily fell and every head turned to look at me. My eyes must have rolled, my nostrils must have flared, and I know I gave a small whine of alarm.”

He kept his head down at breakfast, and for much of the first few days, only looking up when there were other new arrivals, and speaking only when spoken to. It took about two weeks to wrap his head around the school routine but he quickly grew fond of it. “I had settled down by then and knew my way around most of the school, and, of course, had made friends. I was more or less mothered by everyone in my house, and shown great kindness,” he writes.

It didn’t last long. Racial abuse and bullying soon became the norm for him, but he couldn’t understand why. “What was so bad about being black- skinned that I should be abused for it? I recalled that in my early days in Africa, there were many whites living there. Nobody ever abused them for being white, and they never abused us for being black,” he writes in the book.

After the incident in the classics lesson, Onyeama stopped turning the other cheek. “There was something dehumanising and degrading about racial insults. It didn’t feel like an ordinary form of insults,” he tells me. “I didn’t speak to teachers about it. I didn’t speak to anybody about it … I defended myself.” He responded, often with violence.

He says: “I used to smash people’s faces. I didn’t have any qualms about doing that.” It made him deeply unpopular, but he had to stand up for himself. He fell into a toxic cycle, however, writing: “The more unpopular I became, the more the taunting grew; the more I struck out, the more they jeered.”

He is quick to say he wasn’t lonely. His schedule had kept him too busy. “It was a very full life. There was no room for loneliness. There were many forms of recreation. Everything was happening all the time; work, studying, sport,” he says. He excelled at sport, playing cricket, boxing, taking part in athletics and games unique to the school, such as the Eton wall game. He particularly loved being cheered on by his classmates. In those moments he could ignore how he had come to accept that he might be inferior because he was black, writing: “It was comforting and, indeed, a pleasure when my sporting ability was accredited to just that aspect of myself. It was good to know that the white man had some respect and fear for some ‘characteristics’ of blackness!”

To the surprise of his classmates and his teachers, Onyeama did incredibly well in his O-levels. But he wasn’t allowed to bask in his success for long, with one student, who got worse grades than him, spreading a rumour that his pass marks were lowered and his papers were marked more leniently. “I cannot describe how the reaction to my results got on my nerves. It caused me to lie in bed till well past midnight on a number of nights thinking about them. And eventually I concluded that something should be done about it,” he wrote.

This time, he decided he would respond differently. He wrote a letter to the local newspaper expressing his distress at how white people treated black people like him, while taking care to praise the British education system. The letter was published, but no one took much notice of it. Still, he was encouraged to keep writing about his experiences at Eton. He knew then he had an important story to tell.

He was inspired by work of English and African writers such as Graham Greene and Chinua Achebe.

He weaved his experiences at school into a compelling narrative for his first book, Nigger at Eton, published in 1972 by Leslie Frewin Limited. A serialised version of the book was published in a magazine in the runup to the publication date, and sparked outrage at the school. Letters from students’ families and school staff were sent to the publishers.

“I was shaken by the extent that they went to, to suppress it getting published. They did everything they could,” he says. “Imagine a headmaster ringing the publisher and saying, ‘Please, can’t you just bump this book?’”

Others threatened lawsuits. “I’m sure the publishers had grown more grey hair in those few months than all their years … Even the police had come to the office of the publishers,” Onyeama says.

But his publishers held their nerve and went ahead. The response was swift and brutal: Onyeama was banned from ever setting foot on the college campus. “I wasn’t surprised, but I felt outraged. Why the hell did they ban me? Other books went to town on the college, but they [the authors] were not banned,” he says.

The ban felt like an institutional rubber-stamping of the racism he had experienced as a student. “I wrote to the Race Relations Board complaining that the ban was a manifestation of racial prejudice because other books had been written and no action was taken against the authors. Why should they take action against me? My claim was that this is racist. I wrote it as a matter of principle. It made news all over the world,” he says.

The college refused to rescind the ban. Onyeama brushed it off as much as he could and pursued a career in journalism. He worked as a critic at the magazine Books and Bookmen, before becoming managing editor of a publishing house in London.

He published a number of novels, thrillers, including Juju, Secret Society, Revenge of the Medicine Man and Godfathers of Voodoo, in the 70s and 80s. At age 30, he moved back to Nigeria and has lived there ever since.

Finally, in 2020, the headmaster of Eton apologised for his predecessor’s action. “My attitude was: thank you very much,” he says. The ban had been rescinded a few years prior, but Onyeama has not returned to the campus. He doesn’t have any plans to do so. He believed the apology occurred as a result of the unprecedented Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, when 270 towns and cities held anti-racist demonstrations. Historians described it as the most widespread anti-racist protest in modern British history.

A spokesperson for the school said: “Racism has no place in civilised society. Eton has made significant strides since Mr Onyeama was at the school but the racism he experienced was as unacceptable then as it is now. Eton has apologised to Mr Onyeama and has made clear that he will always be welcome here.”

For Onyeama, the Black Lives Matter movement is forcing Britain to confront its imperial past. “It has been forcibly manipulated to that end … Society has to change and I believe it is changing on the back of this onslaught [protest].”

He doesn’t think his experiences in Eton in the 60s would necessarily correlate to the experiences of black and other students of colour attending the college today. But nor does he believe there will ever be equality between black and white people in the UK.

When his eldest son was born, Onyeama’s father suggested he sign his child up to attend Eton. He declined.