‘We can transition to a better country’: a trans Colombian on diversity in ecology and society | Global development

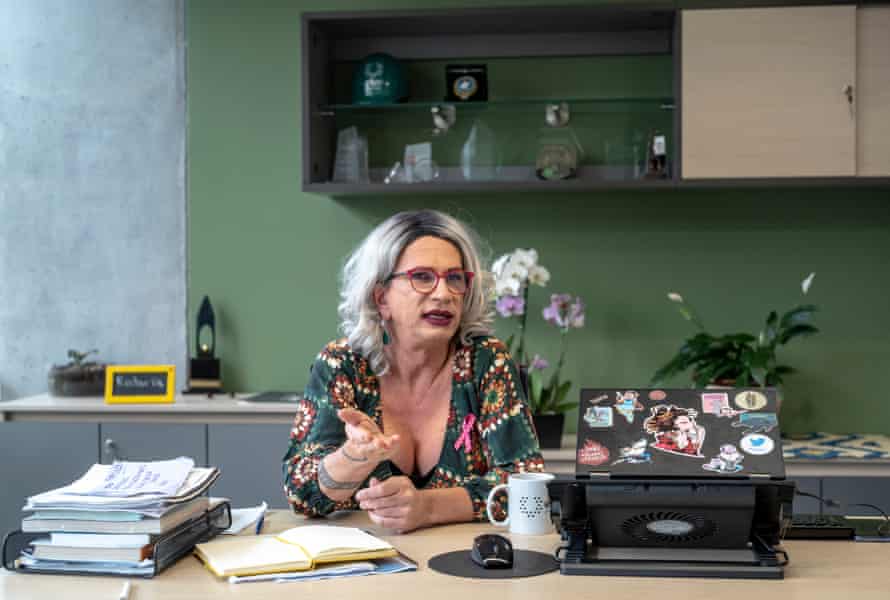

When Brigitte Baptiste walks on to the 10th floor of Bogotá’s Ean University at 9.45am in a plunging dress, knee-high cheetah-print boots and a silvery wig, the office comes to life. She examines some flowers sent by the Colombian radio station Caracol to thank her for taking part in a forum, her co-worker compliments her on her lipstick, and she settles in for a day of back-to-back meetings, followed by a private virtual conversation with the UN secretary general, António Guterres. Later that evening, she flies to Cartagena for a conference on natural gas.

The 58-year-old ecologist is one of Colombia’s foremost environmental experts, and one of its most visible transgender people, challenging scientific and social conventions alike. An ecology professor at the Jesuit-run Javeriana University for 20 years, she has written 15 books, countless newspaper columns, and won international prizes for her work. Most recently, she was appointed chancellor of Ean University, a business school, as part of its push for greater sustainability.

Baptiste was one of the scientists who founded the Humboldt Institute, the leading biodiversity research centre in Colombia, and she was the director for eight years. Much of her research involved rural development, and biodiversity’s role in land management. It took her to communities from the Amazon to the coast.

She saw the “social character of conservation” and the links between war, displacement and environmental degradation. A forceful proponent of a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), she saw a deal as an opportunity for a “great ecological experiment” in the swaths of former Farc territory had been unexplored for years.

Baptiste is a biodiversity expert in a biodiverse country facing destructionfrom deforestation, land grabs, drug trafficking, illegal farming and the displacement of indigenous people. Water pollution from illegal gold mining and inadequate sewage systems have also taken a toll. And this year Colombia was named the world’s deadliest country for environmental defenders for the second year in a row.

Threats to activists concern her more than any other issue, which is what she planned to highlight to Guterres that night in the three minutes allotted to her.

“There is no democracy that can be built on violence, on the extermination of unarmed people,” she says. “There may be many things in Colombia that do not work well environmentally, economically – but all that goes into the background until we are able to respect human rights and guarantee the lives of all Colombians.”

Meetings with world leaders are not uncommon in Baptiste’s career, but the natural-gas conference the following day – where she push energy companies to offset carbon – is a change of pace from the insular world of academia. She decided to take on this role, and the fossil fuel industry meetings that come with it, to apply the results of a lifetime of biodiversity research, and to achieve change from within the system.

Baptiste is a believer in “green capitalism” – that the free market can promote sustainable development.

“There have to be businesses that are not only good for your pocket, they have to be good for people, they have to be good for nature, they have to be good for future generations,” she said. “So that is the idea of sustainable entrepreneurship. That is the contribution that I bring to this school, a search to build that concept in theory and in practice.”

Her views have sparked a backlash from environmental activists, but Baptiste sees her job as encouraging Colombians to value their biodiversity as an economic bounty that can be harvested sustainably. “With businessmen, with bankers, they are always the evil ones at the table,” she says, but stresses: “You have to work with the bankers, the investors, obviously you have to work with the decision-makers, with the politicians, with the civil organisations, and without fear of open debate, whether it’s convenient or not.”

Baptiste has achieved stature in a conservative Catholic country, where violence and discrimination against transgender people are widespread. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, at least 448 LGBT people suffered acts of violence including murder and police brutality.

Baptiste says that now she only faces discrimination on social media, not at work. But does not believes that reflects a higher level of trans acceptance in Colombia. “I don’t think so,” she says.

“I believe that what I have achieved, whether it be a little or a lot, was because I built it before becoming Brigitte publicly.”

Baptiste transitioned in 1998 aged 35, and had already completed a master’s degree and a doctorate, co-founded and directed a non-profit and served on boards.

People respect her because she had earned “guaranteed spaces” before she transitioned, she says, although there are those that feel they “have to put up with Dr Brigitte” with a hint of “yes, la doctora” – she says, imitating her naysayers. “So the gender issue is always used to question the legitimacy of my work.”

“Having a trans woman rector was a bet the university made,” she says. “A generous bet, but also calculated to send a message to society: that this is a different university that can welcome a trans woman as rector.

“But because I already came with an important visibility,” she adds, “who knows if the same thing would have happened with other trans women?”

Daniela Maldonado Salamanca, director of the Trans Community Network in Bogotá, cautions that Baptiste can often be held up as successful in a way that ignores the barriers that prevent most trans women with fewer privileges achieving similar success. “We are very far from being there – socially, economically [and] in access to educational capital,” says Salamanca. “Light years from those processes.”

Baptiste is still misgendered daily, in taxis and restaurants and says trans women have still not achieved “a minimum of linguistic respect” in Colombia.

She is hopeful she will prompt more acceptance.

“If she has been able to do all the things that she has managed to do, a country like this has all the hopes in the world,” says her colleague, executive director of Ean University Billy Crissien.

“We can transition to being a better country, we can transition to being better people, we can transition to being what we want to be as a country,” he says. “Brigitte has shown us a way that wonderful things can be done. I think she fills us with hope for a country like us.”